Long-range Aircraft Detection and Tracking

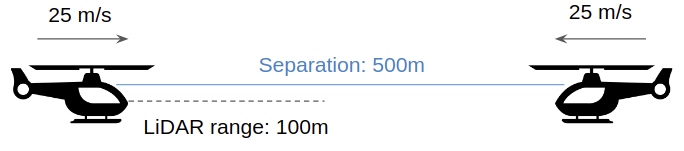

The detect-and-avoid problem is the “holy grail” for small aircrafts and drones that need to fly beyond line-of-sight. Delivery drones in particular need to ensure self-separation from other aircraft to ensure safety. While it may seem that aircrafts could be detected via transponders, they are often not available on many aircrafts and even if they are, the rules and regulations do not make it necessary for them to be switched on at all times. Additionally, other flying objects such as birds, balloons, and other drones don’t have transponders. Therefore it is necessary to detect and avoid these objects for fully autonomous flights. Currently, the only effective sensor for aircraft detection is radar, but it is too heavy and expensive for small drones which have size, weight, and power (SWaP) constraints. These constraints even limit LiDAR ranges to be around 100m. For high-speed obstacle avoidance in dynamic environments, objects must be detected at long ranges (>= 500m) to allow sufficient reaction time. Fig. 1 shows a cartoon illustration of the problem. Thus, the aim of this project is to create a vision-based aircraft detection and tracking system that focuses primarily on long-range detection.

Challenges

Detecting aircrafts at long ranges comes with a lot of challenges. Some of these are outlined as follows:

- Low SnR: Aircrafts or other flying objects at long ranges appear very small and typically have very low signal-to-noise (SnR) ratios (see Fig. 2)

- Poor performance on small objects: The state-of-the-art in object detection keeps changing ever so frequently and the standard benchmarks such as COCO are always being beaten from time to time as more complex models are created. However, the performance of these detectors on small objects (\(< 32^2\) px\(^2\)) is pretty poor as they have low average precision and recall. In the context of our work, the performance is even worse since most of our data consists of small objects.

- Computational constraints: The SOTA detectors are typically very complex in terms of the number of learnable parameters and they usually work on low to moderate image resolutions. Since our context is small objects primarily, we need to operate on high-res 2K images. Such images cannot be processed without downsampling by modern detectors.

Approach

In order to tackle the aforementioned challenges of the detection problem, we created a fully convolutional neural network (FCN) that predicts segmentation maps of objects in the scene. The network consists of a 4-layer deep encoder and decoder with lateral skip connections across layers with similar depth level. The encoder-decoder module is then stacked sequentially three times to create an Hourglass network (which have shown good results in keypoint detection tasks). The advantage of using a FCN is that it can scale across variable resolutions and work on high-res 2K images. It can be thought of as a convolutional sliding window. The model complexity of such a network is also low compared to existing SOTA detectors and can thus be efficiently deployed in resource-constrained embedded systems. In our first results we show that such a network increases the average recall (or the ability to detect all relevant objects) of the system compared to fine-tuned models of existing SOTA detectors such as RetinaNet, YOLO, etc., but at the cost of lowering the average precision (or the ability to minimize the false positive rate). In order to compensate for the loss in precision, we used SORT as a multi-object tracker to get rid of false positives that are not consistent across frames. Since there is a dearth of publicly available datasets for aircraft detection at long-ranges, we initiated a three-stage data collection strategy:

- Simulation data from X-Plane 11 which has ground truth bounding boxes and segmentation masks

- Real-world data from a static fisheye degree camera (along with ADS-B) at KBTP airport.

- Real-world inflight data from a Cessna.

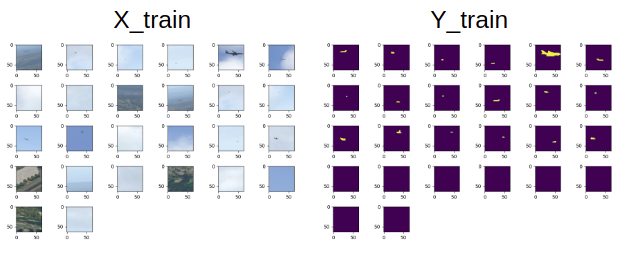

The ADS-B data consists of information about other aircrafts in the vicinity of the camera and hence can be used for post-processing to auto-generate ground truth labels for the real-world datasets. Our team is currently working on creating the autolabeler. Meanwhile, we have trained our FCN detector using data from X-Plane. We train the detector by taking \(64\times 64\) crops from high-res training images. Fig. 3 shows a batch of training data.

Since there is huge class imbalance problem (because aircrafts typically appear as a small speck in the image), we minimize a weighted sum of cross-entropy and DICE loss during training.

First Results in Simulation

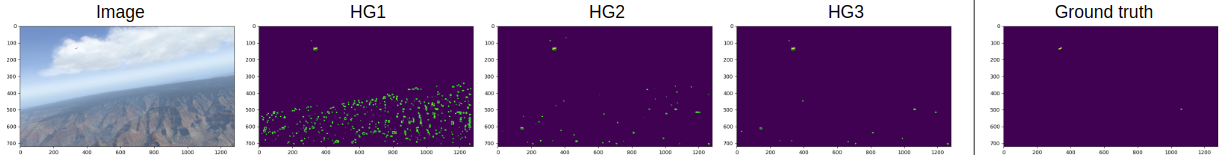

We carried out some qualitative and quantitative study on the simulation dataset. Fig. 4 shows an example result of the hourglass FCN model. We observe that the hourglass model iteratively refines the prediciton (i.e., reduces the false positives) as the layer depth increases.

Qualitative Results

We compared our results with a fine-tuned model of RetinaNet which is a SOTA detector.

We observe that RetinaNet sometimes misses the smaller objects which are picked up by the FCN model.

Qualitative Results

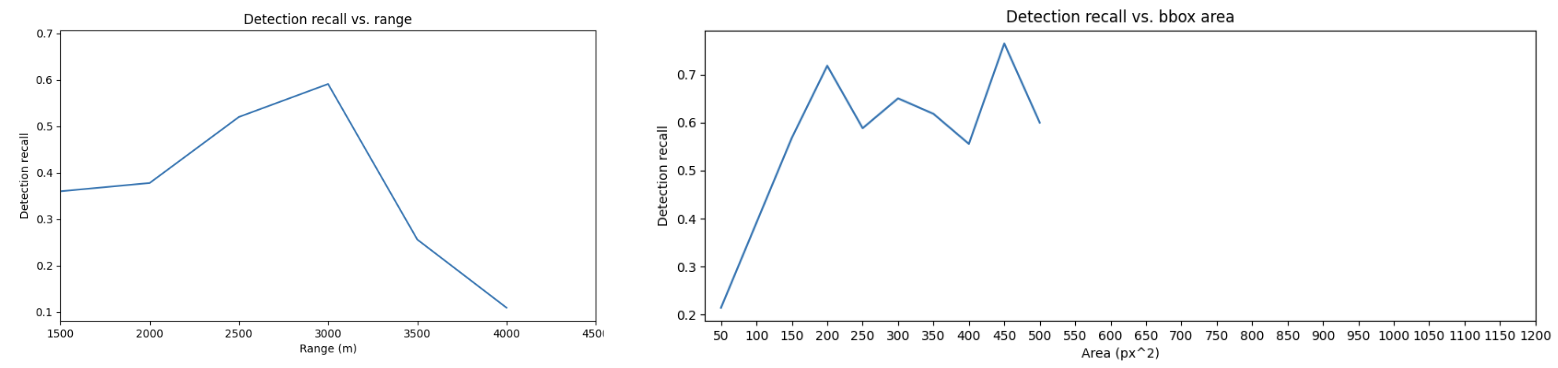

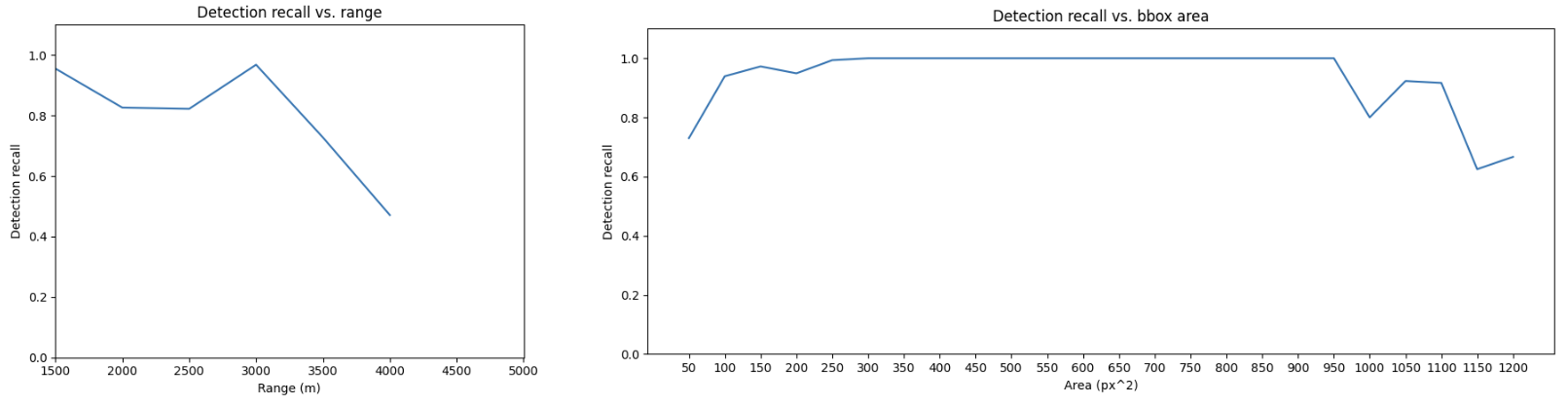

Fig. 5 and 6 shows the quantitative results of the average recall measured against the object range and bounding box area.

We observe that for really small objects (< 100 px\(^2\) area), the FCN model has a much higher recall compared to RetinaNet. The overall average recall for RetinaNet was 0.43 whereas the average recall for the FCN hourglass model was 0.85. The average precision for the RetinaNet was 0.27. The average precision for the FCN model without the SORT tracker is 0.058 (which is extremely low, indicating many false positives) but with the SORT tracker increases to 0.388.

Project Members

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. for generously funding this work.