How do you train AI Pilots?

We need more pilots. AI can help! Advanced Aerial Mobility (AAM) is an inclusive term that covers urban (UAM), regional (RAM), intraregional (IAM), and suburban air mobility (SAM) solutions. All of these proposed solutions have one thing in common: they all envision a future where autonomous or semi-autonomous aerial vehicles are seamlessly integrated into the current airspace system. AAM solutions open doors to significant socio-economic benefits while at the same time presenting challenges in the seamless integration of these systems with human-operated aircraft and controlling agencies.

Today, manned and unmanned vehicles are separated, limiting the utility and flexibility of operations and reducing efficiency. Human operated aircraft follow one of the two rules for operation: Visual Flight Rules (VFR) or Instrument Flight Rules (IFR). The choice of flying under VFR or IFR is typically a function of weather conditions. Under VFR, an aircraft is flown just like driving a car within the FAA established rules of the road. IFR flying on the other hand is typically associated with flying aircraft under degraded weather conditions where separation is provided by the ATC. While a pursuit to integrate AAM can start either under IFR or VFR, automated-VFR operations often have better scalability than automated-IFR operations [1]. Another option involves UTM solutions [2] which in its current iteration only focuses on small unmanned aerial aircraft operating close to the ground (<700 ft) in uncontrolled airspace.

Mastering visual flight rules (VFR) operations for autonomous aircraft has significant operational advantages at unimproved sites, as well as in achievable traffic density compared to instrument flight rules (IFR) or completely separated operations between manned and unmanned systems. For (semi-)autonomous aircraft to operate in tandem with human pilots and ATC controllers under VFR, technological advancements in certain key areas are required.

Specifically:

- Unmanned aircraft should be able to guarantee self-separation even in a tightly-spaced terminal airspace environment;

- Unmanned vehicles should be able to interpret high-level instructions by ATC to meet the expectations of a normal traffic flow;

- Autonomous aircraft need to understand the expected and unexpected behaviour of other aircraft;

- Communications by other pilots and ATC need to be parsed and valid, corresponding responses should be produced; and

- Other aircraft need to be detected and estimated, as well as their future trajectories need to be predicted.

Many of these challenges have parallels in the self-driving industry and the technological improvements there can be leveraged to produce domain specific solutions for AAM. While this is promising, VFR-like AAM integration introduces newer challenges while pushing boundaries on the current state of technology.

Given the domain transfer, we list below certain key areas of development where improvements on current state-of-the-art are needed to enable VFR-like autonomous aerial operations.

Aircraft Detection & Tracking

See-and-Avoid is one of the key tenets of VFR operation. The ability to spot other aircraft or aerial hazards like birds, balloons, gliders etc and execute maneuvers so as to mitigate a collision hazard is critical to successfully deploying AAM solutions in the NAS.

A more detailed update on the recent work is available in this blog post

Intent Prediction

Reasoning about the potential set of future trajectories that other aircraft can take is critical to ensure that the best actions are taken that also minimise risk. Typical prediction methods use short horizons and fail to capture the long term intent of other aircraft. The majority of trajectory prediction work has been explored in the pedestrian and autonomous vehicle domains. Within AAM, goal points such as airports, pilots and ATC communications, and rules of way (such as FAR §91.113) are often known. The use of this explicit source of information as well as implicit sources like weather can help decipher the intent of other aircraft and increase the length of reliable predictions.

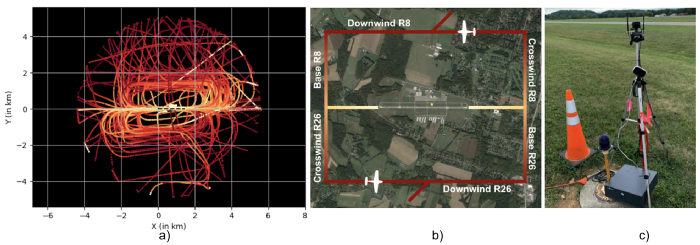

The lack of datasets and baseline methods makes it difficult to conduct meaningful research. Towards this end, we have been collecting traffic data from transponders at select controlled and uncontrolled airports to understand and train models for intent prediction. To capture the influence of weather on pilot decisions, the weather data was also collected by parsing Meteorological Aerodrome Reports (METARs) to gather the relevant sections from the full weather report. We recently published the first chunk of the trajectory data TrajAir along with a baseline method christened TrajAirNet to predict aircraft trajectories trained on the collected data. More information on this is available on this blog post.

Patrikar, Jay, et al. “Predicting Like A Pilot: Dataset and Method to Predict Socially-Aware Aircraft Trajectories in Non-Towered Terminal Airspace.” IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (2022). [Link] [Video]

Safe and Socially-Compliant Navigation

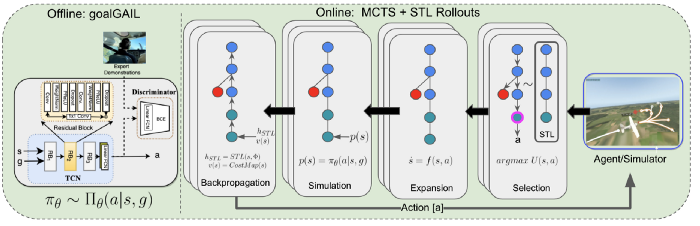

As the FAR rules only specify a rough guideline, autonomous vehicles must be equipped with the capability to make flexible decisions to comply with the traffic norm of arbitrary situations. The idea of social navigation is to learn to follow the observed traffic patterns in a socially-compliant manner. Generating actions that are not only safe but also socially compliant while following rules is thus critical in generating behaviour that is acceptable to human pilots co-habiting the same airspace. We use variants of Monte Carlo Tree Search algorithms that combine learned behaviour with logic specifications like Signal Temporal Logic to enable safe and socially compliant navigation.

Guaranteeing Safety

The safety system ensures that the future trajectory of the aircraft is always safe and a safe fallback trajectory always exists. The safety system also checks plans made by the planning/inference engine to ensure that these plans will not violate safety invariants. Effectively, the safety system serves to encode a safe envelope and guarantees collision-free flight.

Automated Speech Recognition and Production

It is critical to establish clear communication between a human operator/pilot and an AI system in our target problem domain. Specific to the aviation domain is the challenge of understanding and decoding aviation-specific terminology that is different from everyday speech constructions. Other challenges such as radio background noise, incomplete instructions and radio phraseology also need to be addressed.

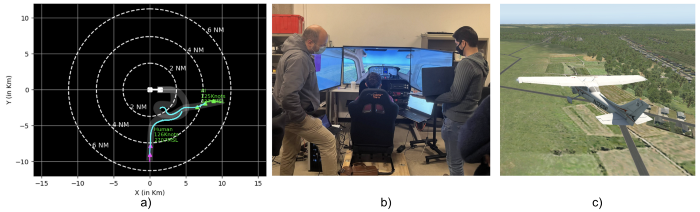

High-fidelity Simulators

For safety critical domains, accurate high-fidelity simulators are required to test algorithms before real-world testing. Given the lack of simulators in the public domain, we designed our simulator christened XPlaneROS. With X-Plane 11 as the high-fidelity flight simulator and ROSplane as the autopilot, we obtain realistic aircraft models and visuals of similar aircraft. The X-Plane Connect Toolbox interfaces between X-Plane and Robot Operating System (ROS) topics. Based on the high-level commands input by the planner, ROSPlane generates the actuator commands for ailerons, rudder, elevator, and throttle, which are in turn sent to X-Plane through XPlaneConnect.

More information is available in this blog post.

Big Picture

We believe that the current understanding of integrating unmanned aircraft within National Airspace System (NAS) needs a more human-pilot centered approach. Pilots and aircraft already operating in the national airspace are important stakeholders in the larger discourse. Technological developments enabling close-proximity safe and seamless operation of manned and unmanned aircraft in a shared airspace need an understanding of the rules and conventions already in place. The NAS is a dynamic environment with in-built flexibility and protocols to handle traffic volumes and emergencies. Our core understanding is then rather than having the current NAS adapt to changing autonomy needs, we need to move towards identifying technological requirements that enable unmanned systems to operate along with humans in a collaborative fashion.

“Our hope is to build true AI-pilots that are indistinguishable from a human pilot to enable a seamless integration within the current NAS.”

Video

The video below gives a general overview of these challenges and potential applications.

Additional Info

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Army Futures Command Artificial Intelligence Integration Center (AI2C).

References

[1] Mueller, Eric R., Parmial H. Kopardekar, and Kenneth H. Goodrich. “Enabling airspace integration for high-density on-demand mobility operations.” 17th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference. 2017.

[2] Aweiss, Arwa S., et al. “Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Traffic Management (UTM) National Campaign II.” 2018 AIAA Information Systems-AIAA Infotech@ Aerospace. 2018. 1727.

Contributors

Jay Patrikar, Joao Dantas, Ingrid Navarro, Ian Higgins, Jasmine Aloor, Parv Kapoor, Milad Hamidi, Jimin Sun, Ben Stoler, Rohan Baijal, Brady Moon, Sourish Ghosh, Dr Jean Oh, Dr Sebastian Scherer